Celebrating Double 8

A small gauge format turns 85

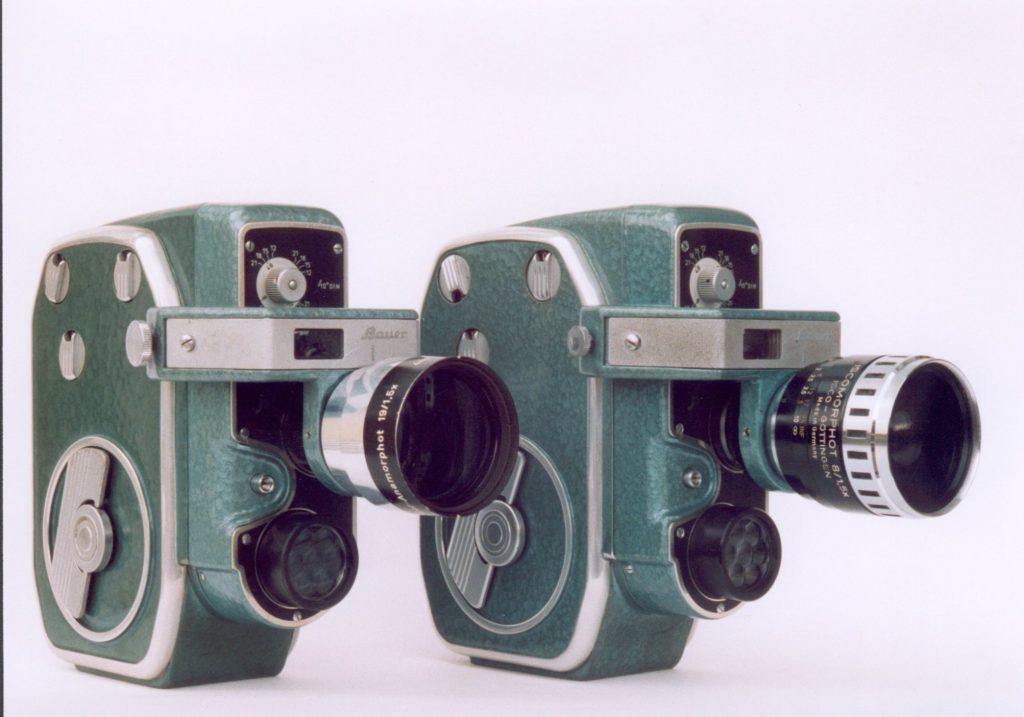

Yes, one could call it old. But it still rattles around in a number of cameras. We offer a salute to Double 8, the small gauge format brought to life by Kodak more than 85 years ago. The film – which comes on little reels that must be flipped when exposed halfway – is still used in quite a number of Leicina, Bolex, Bauer, Agfa and Nizo cameras.

A certain Mr. Eastman began to offer film strips in the USA made from a flexible material called celluloid with a photosensitive coating that replaced glass photographic plates. It did not take long for his compatriot Thomas A Edison to dream up a machine that captured moving scenes on such strips. The prolific inventor quickly noted that the image captured in this manner had to be at least a certain size to achieve a satisfying level of sharpness and grain size. On the other hand, it cost a considerable amount to shoot footage and thus he compromised between the image size and its quality. It seemed most convenient to split commonly manufactured 70 mm film stock into two 35 mm strips with perforations on both sides for motion picture use. One realizes how sharp the decision was by the fact that this film has remained in use until today – about 120 years – with only slight changes as a uniform worldwide film standard.

Many film pioneers adopted this standard and shot on 35 mm film, as did early hobbyists who earned nothing from “moving pictures.” However, it was damn expensive to shoot in this format, and it took only a few years until resourceful thinkers decided to further reduce the film width, and thus to scale down the image area. In the end, it was not necessary to show a private film in a living room at the same width as in a real cinema. And so came about the early small film formats. Englishman Birt Acres created one of the first around 1898 – an edge perforated 17.5mm-wide film – and still other formats soon followed. Among them: 28 mm (Pathé-Kok, 1912), 22 mm (Edison Home kinetoscopes, 1912), 21mm (Reulos, Goudeau and Co. Mirograph, 1900), 15 mm (Gaumont Chrono de poche, 1900), 12.7 mm (Prestwich junior, 1899) and 11 mm (Bradley Duplex, 1915).

Amateur film slims down

The 17.5mm format quickly emerged from this confusion of formats to become the most popular among amateurs. It took until 1921 for Pathé to create the relatively inexpensive 9.5mm format, which spread quickly. There was also a reversal stock available in this “small gauge” format that was processed directly as a projection-ready positive, reducing costs even further. It was no longer necessary to produce expensive prints from the original negative. In addition, one could now present home made films in optimum quality, because – as everybody knows – certain sharpness and resolution losses are unavoidable in every analog copying process. Of course, these losses are avoided when projecting the reversal original. Without this progression to reversal film, the further reduction of shooting formats that came in following years would have been barely conceivable.

Before that was to occur, however, Kodak released their 16mm-wide film in 1923 and stepped into the amateur market to compete directly with the 9.5mm format, which was clearly cheaper thanks to its smaller width. A violent dispute soon swirled among amateurs about which format was superior, especially in France where, even today, the center-perforated Pathé creation remains exceedingly popular, while 16mm was soon favored in the USA. It was intended originally for amateurs, however it grew over time into a predominantly professional format for educational films, documentaries and commercials. Science increasingly relied on 16mm and it was helped by the appearance of television to report current events and the widespread use of the format to produce TV serials. It turned out that the generous dimensions of 16mm, which had caused its initial cost disadvantage, became useful later on with technical advancements. When sound conquered the previously silent world of celluloid, perforations were eliminated from one side of the previously double perforated film to make room for a full 2.5mm wide soundtrack without having to reduce the frame size. Television’s shift to the 16:9 wide format was handled easily by 16mm; the soundtrack area was simply incorporated into the image frame, widening its aspect ratio from 1:1.37 to an opulent 1:1.66, or so-called “Super 16,” which has proven well suited to 16:9. Nine-point-five, the “Format of the golden middle,” could not keep pace with this development.

Double Eight

However, shooting on 16mm or 9.5mm was still a rather expensive hobby in the 1920s and remained affordable only to a few wealthy enthusiasts. When the worldwide economic crisis led to the Depression, the purchasing power of the population could not keep up. Thus, Kodak made plans to modify its double perforated sixteen millimeter film once again. The number of perforations was doubled and the frame advance was reduced from 7.62 to 3.81mm, while the image size was scaled down from 67.2 mm² (9.6 x 7mm) to a meager 14.8 mm²(4.5 x 3.3mm), so that two images now fit side-by-side on the 16mm-wide raw film, and the format was christened “Double 8.” The area of a single frame was only one quarter the size of the 16mm format, however improved film stock and the use of reversal film projection resulted in sufficient sharpness for a picture width of 1 meter or slightly more without the film grain becoming too noticeable. Consequently, most amateur filmmakers of the time were content with the format. However, they quickly bumped into the limitations of this shoelace format if they wished to present their work in front of a larger audience.

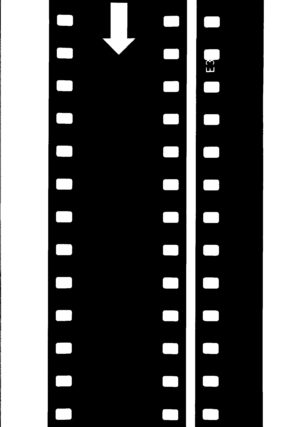

To shoot Double 8, a 16mm-wide film is run through the camera twice with only one half of the film exposed on the first pass. Once the film is completely wound onto the camera-specific takeup reel, it is turned and reloaded onto the feed reel for a second pass through the camera. Most manufacturers incorporated differently shaped holes on each side of their reels to make incorrect insertion impossible. After loading, the roll is ready for exposure of the other half of the film, which is once again wound onto the original reel. One then sends the film away for processing. After development, the still 16mm-wide film is split into two strips – typically 7.5m long – which are spliced onto a single 15m reel and returned to the home movie enthusiast. Double 8 is purely a shooting format – the projector runs only with 8mm wide film.

The “Double 8” format is also known as “Double Run 8mm,” “Regular 8mm“ or “Standard 8mm.” When Kodak Double 8 was launched in 1932, the resourceful men from Rochester immediately released suitable shooting and projection devices. The quintessential focus of the system was the Ciné Kodak 8, a handy camera with a simple rangefinder integrated into the handle and a spring motor built into the cog drum which could pull about two meters of Double 8 film at a shooting rate of 16 fps. The matching Kodascope 8 projector sold for the same price and there were a number of accessories such as splicer, rewinder and a viewer. However, the chief attraction was the relatively low price to shoot film; it cost more than twice as much to shoot the same run time of 16mm film.

A piece of your life for the cost of a snapshot

A brochure introducing the Ciné Kodak Eight declared that a “new era of amateur cinematography” had begun, and everyone who takes photos can also shoot film. They calculated that a medium-length scene cost less than a single 6 x 9 cm black & white photograph.

The Nizo 8 E arrived on the market in 1933 as the first European Double 8 camera. Other manufacturers followed, and by the middle of the decade the success of the new format could no longer be contained. In the USA, manufacturers also started to build cameras which were designed for 8mm wide film, sold as “Straight 8,” “Single 8” or “Super 8(!),” although the last two names had nothing to do with the subsequent small format film systems launched by Fuji and Kodak in the 1960s.

With the goal of skirting patent problems with Kodak, Agfa presented the Movex 8 – also configured for 8mm-wide film – at the 1936 Leipzig fair. The shooting stock, often referred to as “Easy 8,” was 10 m long and came in a special cassette that fit only this type of camera. Indeed, the Movex cassette did not offer film backwinding capability, however it was significantly less complicated to load than the Double 8 reel, which always had the added threat of light leaks. Some other manufacturers built cameras for this system for a short while, although it had a serious disadvantage: In 1935/36, the “Big Yellow Father from Rochester” introduced Kodachrome – the best and smallest grained color reversal film of its time – in 16mm and Double 8 formats, but not in the Movex cassette.

With the goal of skirting patent problems with Kodak, Agfa presented the Movex 8 – also configured for 8mm-wide film – at the 1936 Leipzig fair. The shooting stock, often referred to as “Easy 8,” was 10 m long and came in a special cassette that fit only this type of camera. Indeed, the Movex cassette did not offer film backwinding capability, however it was significantly less complicated to load than the Double 8 reel, which always had the added threat of light leaks. Some other manufacturers built cameras for this system for a short while, although it had a serious disadvantage: In 1935/36, the “Big Yellow Father from Rochester” introduced Kodachrome – the best and smallest grained color reversal film of its time – in 16mm and Double 8 formats, but not in the Movex cassette.

At that time, the idea of accommodating the shooting stock in an easy to use and light-safe cassette seemed to be floating in the air. There was already something similar available for other formats (16mm and 9.5mm) and thus it came as no particular surprise when Siemens and Halske introduced a removable magazine at the 1936 Leipzig fair that took 7.5 m of Double 8 film on a reel. Soon afterwards, Zeiss Ikon followed with a magazine designed for their Movikon K8. These developments did not give Kodak a chance to rest, and in 1940 they presented their own removable metal Double 8 magazine that earned support from other manufacturers. Many of these practical removable cassettes stayed on the market for quite a while, however they slowly disappeared because no one could agree on a uniform system.

At that time, the idea of accommodating the shooting stock in an easy to use and light-safe cassette seemed to be floating in the air. There was already something similar available for other formats (16mm and 9.5mm) and thus it came as no particular surprise when Siemens and Halske introduced a removable magazine at the 1936 Leipzig fair that took 7.5 m of Double 8 film on a reel. Soon afterwards, Zeiss Ikon followed with a magazine designed for their Movikon K8. These developments did not give Kodak a chance to rest, and in 1940 they presented their own removable metal Double 8 magazine that earned support from other manufacturers. Many of these practical removable cassettes stayed on the market for quite a while, however they slowly disappeared because no one could agree on a uniform system.

By 1958, things had progressed to the point where there were three different versions of the Nizo Exposomat 8: The Model 8 T for Double 8 daylight reels, the Model 8 M for the Kodak magazine and the Model 8 R for the Nizo self-loading quick changers. Neither the camera manufacturers nor the photo dealers would have been pleased with the sutuation, since each film type had to be stocked in the various cassette formats. Still, Bell & Howell presented a selfloading cassette for the Autoload Reflex in 1964 which received some positive attention, but failed to became a standard. When Agfa introduced the high-end Movex Reflex camera at that was able to do everything that a filmmaker could dream of, they also introduced with a selfloading cassette which was of course designed especially to fit that particular camera model. Eventually, the demand for a generic cartridge was met by Kodak and Fuji with the creation of Super/Single-8.

By 1958, things had progressed to the point where there were three different versions of the Nizo Exposomat 8: The Model 8 T for Double 8 daylight reels, the Model 8 M for the Kodak magazine and the Model 8 R for the Nizo self-loading quick changers. Neither the camera manufacturers nor the photo dealers would have been pleased with the sutuation, since each film type had to be stocked in the various cassette formats. Still, Bell & Howell presented a selfloading cassette for the Autoload Reflex in 1964 which received some positive attention, but failed to became a standard. When Agfa introduced the high-end Movex Reflex camera at that was able to do everything that a filmmaker could dream of, they also introduced with a selfloading cassette which was of course designed especially to fit that particular camera model. Eventually, the demand for a generic cartridge was met by Kodak and Fuji with the creation of Super/Single-8.

Each one more beautiful than the last

The camera manufacturers who had placed their hopes on the Movex cassette, and eventually the Agfa supporters, all subsequently shifted to Double 8 reel film. Now amateur film reached a level of popularity like never before and the industry built one wonderful camera after another as equipment constantly improved. Where previously the amateur filmmaker was required to find the correct aperture setting using a Stop Table on the outside of the camera, now semi or even fully automatic exposure control was becoming widespread, so that even technically inept amateurs could film easily.

The creativity of camera designers seemed to know no bounds, and Zeiss Ikon showed themselves to be especially unconventional with the creation of a new Movikon in landscape format. High-end products like the Nizo Heliomatic satisfied even the most demanding filmmakers. Many of the better-equipped models allowed the optics to be exchanged for other focal lengths. However, the industry provided telephoto adapters and wide angle adapters so that even owners of cameras with permanently attached lenses could experience the pleasure of focal length changes and the creative possibilities that followed.

Even shooting black & white movies with filters had been made easy. There were special double filters with integrated grey disks for models like the Bauer 88B or E Special which automatically compensated to ensure that the light supplied to the exposure meter was reduced by precisely the amount absorbed by the filter in front of the camera optics. One saw demanding amateurs with not only wide-angle adapters and tele-adapters, but also working with a range of different filters. In addition, some spectral filters like the Skylight soon became preferred equipment to reduce the blue sting of bright sunlit scenes and an amber filter made it possible to shoot artificial light film in daylight – a procedure that became less alien with the later Super 8 format. Cameras like the Bauer 88 H followed sporadically, with a built-in filter turret that contained a grey Skylight and an amber filter; it was a very elegant thing.

Even shooting black & white movies with filters had been made easy. There were special double filters with integrated grey disks for models like the Bauer 88B or E Special which automatically compensated to ensure that the light supplied to the exposure meter was reduced by precisely the amount absorbed by the filter in front of the camera optics. One saw demanding amateurs with not only wide-angle adapters and tele-adapters, but also working with a range of different filters. In addition, some spectral filters like the Skylight soon became preferred equipment to reduce the blue sting of bright sunlit scenes and an amber filter made it possible to shoot artificial light film in daylight – a procedure that became less alien with the later Super 8 format. Cameras like the Bauer 88 H followed sporadically, with a built-in filter turret that contained a grey Skylight and an amber filter; it was a very elegant thing.

In an effort to simplify filming for amateurs and to raise the price of cameras, the industry had lots of ideas. The triple lens turret was very useful. In addition to the normal lens, it offered wide angle and telephoto optics. One no longer had to screw on single adapters or lenses anymore, since the revolver could be rotated until the desired optics were in the shooting position.Few filmmaker wishes remained unanswered, and the biggest demand was for infinitely variable focal length lenses. However, zoom optics were already waiting in the wings.

The image widens

Before we explore zooms, it is necessary to explore an extremely interesting phase of amateur film that caused a sensation for a certain time, before falling largely into oblivion once again. At the time, CinemaScope had lured the public in droves with immensely widened cinema screens. Many amateur filmmakers viewed this intriguing technical development with a mixture of enthusiasm and envy, as did the lens manufacturers, especially Moeller, Old Delft in Holland and Isco in Goettingen. They created special wide picture adapters, known to the experts as “anamorphic lenses,” and disrespectfully referred to by the layman as “squeeze lenses,” which allowed the small format filmmaker to widen his shots. Still, the frame size of tiny 8mm did not allow an aspect ratio like real CinemaScope, which was initially 1:2.55 and later 1:2.35, a horizontal expanse that would have demanded far too much from this shoelace format. As a result, one had to be content with “amateur CinemaScope” with an aspect ratio of 1:2, which is still wider than today’s ever-so-hyped 16:9 television format (about 1:1.77).This means that the anamorphic lenses had a compression factor of 1.5x for small format cameras, while a professional CinemaScope adapter compressed the image by a factor of 2x. To show the film, a suitable anamorphic lens – often the same one used while shooting – was placed in front of the projection lens to “iron out” the image compression and reveal an image widened by around 50% or 100% on the screen.

The first wide screen adapters for amateurs came from Möller, who introduced a fixed focus anamorphic lens which was prefocused to 4 m and – according to the manufacturer’s specifications – captured everything “from 2m to infinity” sharply. The ISCO- Einstellanamorphot (adjustable anamorphic) turned out to be a substantially better multi-purpose adapter, since it offered exact focal settings from 50 cm to infinity. These optical adapters allowed cameras with simple fixed focus lenses (such as the Bauer 88B and 88F) to offer the pleasure of adjustable focus.

Many filmmakers shot widescreen films enthusiastically, and were pleased to be able to add anamorphic capability to their camera while attempting to meet the compositional requirements of the very wide image. However, when zoom lenses hit the amateur film world, things suddenly became very quiet with regard to “little man’s CinemaScope,” as the former widescreen fans quickly realized where they stood. Camera manufacturers responded to their inquiries by explaining that widescreen technology would be extremely expensive in conjunction with attached zoom lenses. The widescreen enthusiasts gradually returned to normal images and discovered that newer projectors were not equipped for the installation of anamorphic lenses to show old widescreen films. As a result, they were forced to figure out their own homemade solutions, which were not always optimal.

Excellent devices from good homes

The final great innovation for 8mm filmmakers was the zoom lens. It offered the possibility of infinitely variable focal length without changing the objective. Unfortunately, many amateurs did not recognize this as the true strength of these miracle optics. They saw zoom primarily as an instrument for optical dolly shots and zoomed to the end stops. On most cameras, the lens was permanently integrated into the optical system to allow the incorporation of an automatic aperture mechanism without higher cost. Particularly high-quality cameras such the Camex Reflex 8 CR, the Bolex H8 and many gems from Beaulieu offered interchangeable lenses that made these not-so-cheap models objects of desire for especially ambitious filmmakers.

However, the projectors of the era should not be completely forgotten, even if they were configured not for Double 8, but for projection-ready Double 8 mm strips. One of the most widely made models was the Eumig P8 from Vienna, which enjoyed lengthy popularity. Many are still functional today, thanks to their indestructible construction. The company also gave us one of the first 8mm magnetic sound projectors, the Eumig Mark-S, which slowly started the migration away from the habit of using a parallel tape recorder to capture sound.

However, the projectors of the era should not be completely forgotten, even if they were configured not for Double 8, but for projection-ready Double 8 mm strips. One of the most widely made models was the Eumig P8 from Vienna, which enjoyed lengthy popularity. Many are still functional today, thanks to their indestructible construction. The company also gave us one of the first 8mm magnetic sound projectors, the Eumig Mark-S, which slowly started the migration away from the habit of using a parallel tape recorder to capture sound.

The Siemens 800 was a particularly nice effort, although it was found in relatively small quantities because of its quite high price. In the beginning, the machine included a high voltage 110V / 500W lamp – the same bulb used in the 16mm Siemens 2000. Later variations used an illumination system with a 12 V /100 W ellipsoid reflector lamp which has been out of production for a long time and is now hard to get. Nevertheless, this projector – with its two separately controlled grip arms and 3-blade shutter which could be interchanged with a 2-blade mechanism – is still the crown jewel of every 8mm device collection. For audio recording, there was an extremely reliable double system 8mm tape drive (perforated magnetic tape; cordband), which could be attached to the rear. Unfortunately, no other manufacturers adopted this process, so the projector remained a loner and the projector was offered awkwardly with the sound drive even after the introduction of Super 8.

The Siemens 800 was a particularly nice effort, although it was found in relatively small quantities because of its quite high price. In the beginning, the machine included a high voltage 110V / 500W lamp – the same bulb used in the 16mm Siemens 2000. Later variations used an illumination system with a 12 V /100 W ellipsoid reflector lamp which has been out of production for a long time and is now hard to get. Nevertheless, this projector – with its two separately controlled grip arms and 3-blade shutter which could be interchanged with a 2-blade mechanism – is still the crown jewel of every 8mm device collection. For audio recording, there was an extremely reliable double system 8mm tape drive (perforated magnetic tape; cordband), which could be attached to the rear. Unfortunately, no other manufacturers adopted this process, so the projector remained a loner and the projector was offered awkwardly with the sound drive even after the introduction of Super 8.

The end of an era

As attractive as all these cameras and projectors were, the Double 8 format suffered from a birth defect right from the start. If you examine Double 8 film under a magnifying glass, you immediately notices that it is indeed a descendent of 16mm film. While the number of perforations is doubled, their width corresponds exactly to those used by the format’s bigger brother. It was originally desirable to have it this way to allow both types of film to be processed in the same developing machines. When comparing 16mm and Double 8 against the projection-ready 8mm film, the eye quickly spots that the perforation demands more than 1/3 of the film width and leaves an unreasonably small area for the image. This flaw struck eagle-eyed filmmakers quite early on, and there were all kinds of clever proposals to eliminate this disgrace. In February 1963, shortly before the introduction of Super 8, the editors of schmalfilm tackled the subject in an article entitled, “The gigantic perforation.”

This perforation, which was immensely oversized for 8mm film (1.83 mm wide) was denounced over and over and eventually led to the release of Super 8 and Single-8. These new amateur film formats incorporated a perforation that was a mere millimeter wide (0.914 mm), while enlarging the frame area by nearly 50% over Double 8. This signaled the end of Double 8, and the production of new models focused on the new Super 8 format. Many Double 8 fans greeted Super 8 with healthy mistrust in 1965, but they failed to hinder its success which propelled small format film to new heights that did not return to earth for another 20 years.

The industry did not want to leave those who had been working with Double 8 standing in out in the cold, so they built projectors which could run both the old and new formats. This smoothed the transition to Super 8, particularly since Double 8 enthusiasts can still find suitable film stock for their robust cameras today.

Originally, the shelves were filled with a rich variety of black & white and color reversal films. However, their availability shrank over time. Agfa ceased production of black & white Double 8 film in 1969, and color in 1973. Their competitor Ferrania-3M did the same. Only Big Yellow continued to deliver Double 8 color film until 1992; initially the great Kodachrome II, and then Kodachrome 25/40 starting in 1975.

Originally, the shelves were filled with a rich variety of black & white and color reversal films. However, their availability shrank over time. Agfa ceased production of black & white Double 8 film in 1969, and color in 1973. Their competitor Ferrania-3M did the same. Only Big Yellow continued to deliver Double 8 color film until 1992; initially the great Kodachrome II, and then Kodachrome 25/40 starting in 1975.

You might guess that the old Double 8 cameras have been mothballed after all this time without film. However, it was far from unobtainable! Small companies quickly leapt to the challenge in various countries and re-cut film available in other formats into Double 8 and rushed to offer it to the ceaseless 8mm filmmakers. Even Kodachrome is still available, although other names are more common. The raw stock often comes from Fuji, Foma or other manufacturers. It is relatively simple to re-perforate commonly available 16mm material for Double 8.

If you still own a functional Double 8 camera, there is no reason to toss it onto the scrapheap. Film is still available for the format – mainly made by Foma (Fomapan R, see here: https://www.super8shop.de/en/product/sample-product/fomapan-r-2x-10m-ds-8/). Indeed, the stigma of its unfavorable frame size remains, but the integrated metal pressure plate offers a tremendous advantage. The 8mm format brought us an abundance of beautiful cameras into which a multitude of designers poured all their skill. The Double 8 era was truly breathtaking!